So ... it

seems there has been a proper furore and rush of blood to the heads (sorry ... that was a feeble attempt at a haemodynamics link ) of some folk, over the use/choice of a

word in the @thecsp (UK)

PR campaign ‘Love Activity, Hate Exercise’.

The whole affair highlights the

incredibly emotive power of words/word choice and how interpretation is entirely

dependent on perspective and context.

|

Love activity, Hate exercise?

Image: CSP http://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/practice/public-health-physical-activity/love-activity-hate-exercise |

As

well as promoting movement and physical activity (and exercise), one of the key

messages of both campaigns seems to be that #Exercise

adherents and promoters (I would place myself into that category) ... may find

it challenging to see things from a non-exerciser's perspective ... The suggestion

being that anything that helps facilitate a greater understanding of the

patients perspective, and helps start a conversation, can only be helpful,

surely?

That

said, HATE is an incredibly emotive word and I've always encouraged my kids

never to use it ... so I see the antipathy to its use. However, I can see the

value in backing the #LoveActivity

campaign, because if a patient uses the 'hate' word (and they do) as therapists

we have to have the empathy and skills to deal with that ... It is a psychosocial

phenomenon of our times and something we challenge our students to consider the

realities of.

Seems

like Marmite ... you'll either LOVE it, OR H*** it … AND quite frankly, it is entirely

your choice.

|

| Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dontcallmeikke/3306300654 |

The

ugly divisions that have ensued within the profession (and are still going on) are

also a psychosocial phenomenon of our times, and times past. The only thing

that has really changed is the platform and the players. There have always been

differences of opinions and schools of thought. Social media has simply opened

up debate and discussion to all. That is probably a good thing in a profession

that is striving to change. However, what is clear is that it becomes very easy

to create divisions, factions/tribes and to polarise opinion.

Q. Is that a good thing?

A.

Maybe, maybe not. It depends on the context, perspective (and perhaps motive).

In Jeremy

Lewis and Peter O’Sullivan’s recent BJSM editorial ‘Is it time to reframe how we care

for people with non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain?

They

suggested, “… Evidence informed self-management is the key. To achieve this,

the efforts of many institutions, including educational, healthcare, political

and professional organisations, health funding bodies and the media, need to be

involved.” In essence what they were saying was that there is a need for a

cohesive and consistent message from ALL invested and concerned with improving

patient care. Those cohesive messages

whether they are about assessment/treatment methods/modalities, or exercise/advice

interventions, need to be evidence informed, consistent and convincing. Most folks

are cognisant with the concept that nothing is written in stone, evidence

evolves, and what we seemed quite certain about today, may be proved entirely

wrong tomorrow.

Q. So, where does that leave

us?

A.

It leaves us all, frantically trying to make sense of an ever shifting

environment, conflicting stories, personal opinion, interpersonal/tribal

battles and #FakeNews.

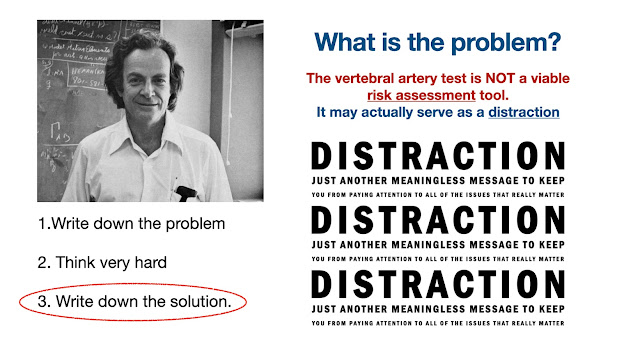

Q. OK … so what is the

solution?

A.

That is the 64 million dollar question!

It

is also a question I been battling with for a while. Unfortunately, I can’t

pretend to know the answers either … and I expect the answers will differ

anyway, depending on a range of factors, not least the psycho-sociological

environment from where you view all of this. It is my guess that regardless of

your environment most folks will feel elements of uncertainty and confusion,

whether they are (Physiotherapy) clinicians, researchers, teachers/academics or

indeed patients … and it is worth reminding ourselves (wherever we may fall on

that spectrum) that everyone his their own ‘coal face’ and everyone contributes

to the landscape highlighted by the BJSM editorial.

Here

are a few tips or considerations on how to survive in a constantly changing

environment.

1.

Evolve or die: Sounds a bit harsh, I

know, BUT it is a fact of life. History reminds us, that emerging research has

challenged much of our previously accepted knowledge. In addition, much of what

we believe to be true today will become obsolete within a decade or so. It may be helpful to recall that one previous profession linked to ours did eventually get 'wound up' ... they were known as Remedial Gymnasts.

2.

Be less dogmatic: 1. Above, dictates that

dogmatic thoughts or deeds are unlikely to yield results. No system, method,

school of thought works for all of the people all of the time. There are

(pretty much) always exceptions to any rule.

3.

Get comfortable in the

grey: This

is difficult but essential. Most folk prefer black and white answers of

absolute certainty. I’m sorry, but 1 & 2 above dictate that you may have

chosen the wrong profession if you expect or demand that from Physiotherapy.

4.

Be less divisive and

collaborate: When Lewis & O’Sullivan

(BJSM)

said “the efforts of many institutions, including educational, healthcare,

political and professional organisations, health funding bodies and the media,

need to be involved (in change, sic)”… they meant it! Clinicians, and patients,

clearly play a vital part and social media opinionists require a sense of

social responsibility, if they really want to be effective change makers.

5.

Don’t buy into phoney wars:

Physiotherapists

have always been caught up in hierarchical factions and been led by colourful

gurus, still (unfortunately) are. Why there is a need to create divisions’

remains a mystery, perhaps it is the frailty of humans? Regardless, the created

phoney wars, appear to serve no one (except those who create them) and simply

retard progress.

6.

Recognise how language can be manipulated: Controversial … not really, just a reality of life in a World of

fake news. Unspeak is a language

style adopted by commentators who wish to make counter arguments untenable. It is a

tactic (weapon) used by those who prefer to perpetuate division or phoney wars. It

relies heavily on opinion (not evidence) and emotion. It is created to make any

alternative viewpoint seem abhorrent or untenable.

7.

Be … pro-honesty,

pro-community, pro-evidence and anti-division (if you really have to be anti-anything): See 6 above and ‘Unspeak’

below.

Q. OK … so what is

‘Unspeak’ and what on earth has it got to do with physiotherapy?

A. Unspeak

is a term that was coined by Journalist Steven Poole in 2007 in his book ‘Words

Are Weapons’. Unspeak has crept imperceptibly into the narrative of

Physiotherapy discussions. It is a tactic to make controversial issues

unspeakable and, therefore, unquestionable.

This VIDEO is an interactive

documentary investigating the manipulative power of language. Watch it! Once

you have recognised it, you will always be able to spot the tactics in ANY

environment.

|

| https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M-iwVXr-mJ8 |

There

are many examples; perhaps the easiest to follow is the pro/anti abortion one. Pro

abortion campaigners began to call themselves ‘pro-choice’ … after all everyone

wants CHOICE, don’t they?

But

… in a clever manipulation of language, the anti-abortion lobby quickly

countered their opposition, by referring to themselves as ‘Pro-Life’ … because

who on earth would argue that they were ‘Anti-LIFE’?

Q. Yes, and …?

A.

Oh sorry. The reason this came up again, is because it has been part of the

narrative of physiotherapy for a little while now, to demonise certain elements

of physiotherapy practice by referring to them (without evidence) as ‘harmful’

… or ‘low value’. It has been highlighted again by the recent and ongoing 'Hategate' controversy.

Q. So what is the problem

with that … ?

A.

Well here at last, we get to the point … ‘harm’ is a very emotive word, a

little like ‘hate’, in fact the two may be associated or linked e.g. “the

deaths and horrific injuries (harm) that occurred in the fight, were associated

to the long standing hatred between the two gangs”. An extreme example YES, but

one that illustrates that harm can truly be emotive.

To allocate the ‘harm’ to

a harmless modality (name your own example HERE .................…………..) seems somewhat disingenuous

to say the least. If a modality has been shown to be ineffective or

uneconomical (from a health economics perspective) then say so, that is fine. When

I railed against this on SoMe lots of folk misinterpreted my stance, but since

the ‘hate controversy’ has blown up, we are back full circle to the harsh reality of word

choices.

Q. Can you give me an

example?

A.

Sure. At my particular ‘coal face’ (UG and PG Physio/Sports Rehab Teaching), we have to try and make sense of all of the

incoming information (from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, SoMe

commentators etc.) and contextualise and disseminate it for inquisitive minds. With the luxury of both time and resources, we

do our best to keep up to date, and appreciate how busy clinicians must find

that really challenging. We also know a lot more about how the words we use in a clinical environment with patients can affect them adversely (or not, depending on choice).

At

the end of the day, very few people WANT to do harm. So when a physiotherapy or

Sports Rehab’ student asks if say, muscle knots or massage

are ‘harmful’ because they heard it said on the Internet. We try to add some

context and perspective, and use that as an opportunity to develop critical

thinking.

|

| Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jeanlouis_zimmermann/3042615083 |

Q. Yes, but you know this

is not about physical harm, it is about adverse psychological effects. So what

is your problem?

A. OK that’s fine, I see that they do occur (in

some cases). So why not refer to them as ‘adverse psychological effects’ or

delays to diagnosis/appropriate care? I just feel uncomfortable (in the same way as those who who perfectly understandably, dislike the use of the word 'hate') with the use of the

language as a tool for demonisation, particularly in the absence of either a

clear definition or any evidence to support the statements that are made.

Q. The term ‘harm’ is used

in psychological literature isn’t it?

Q. OK … what about the word

‘Hate’ in the CSP #LoveActivity #HateExercise campaign, it has been suggested

that this has made exercise “unspeakable”?

A. Yes,

I saw that, and is an interesting turn of events. Because of my interest in the use/misuse of language I have

thought about it really hard. I think it is important to look at the context in

EVERY situation. First of all what is the intent? If the intent were (for some

reason) to demonise exercise, then you could perhaps make that argument. BUT,

as I understand it the campaign … it’s not trying to do that. Rather, as I said

earlier, the CSP campaign appears to be a well-intentioned strategy to raise the

awareness and importance of physiotherapists prescribing physical activity and exercise.

Whilst at the same time, like the American Heart Association information, it

recognises that a large part of the population are not natural exercisers. The

question mark appears to make that explicit, as a number of commentators have

suggested. However, those who are opposed ethically, to the word 'hate' (and many are) will always find it difficult to get behind a campaign no matter how well intentioned, that contains that particular word.

Q. So how do we all move

forward from here?

A.

Well personally, I'd suggest that it has become abundantly clear that the power of language can unite or divide and perhaps everyone has learnt from that. Going forward, we should all be better equipped to spot the manipulation of language in narratives, wherever we may encounter it. As for the rest, I would hand this back over to the two evolving sages, Lewis & O’Sullivan …

They suggested we should:

1.

Frame past beliefs against new evidence.

2. When

in conflict, learn to evolve with the evidence.

3.

Acknowledge the limitations of current surgical and non-surgical interventions for

persistent and disabling non-traumatic presentations.

4. Upskill

and reframe of practice, language (in all domains, sic) and expectations.

5.

Consider aligning current practice with that supporting most chronic healthcare

conditions.

6.

Better support those members of our societies who seek care.

7.

Be more honest with the level and type of care we can and should currently offer,

and the outcomes that may be achieved (Lewis

& O’Sullivan BJSM, 2018).

To

do all of those things, will require a radical change of mind set which aligns

with the current challenging health care climate. It is a global challenge that

is well recognised and which Physiotherapists the World over can rise to … IF and perhaps only if, they can bring

themselves to end the self-perpetuated, unnecessary conflicts.

Q. Alan … doesn’t that

sound a little Utopian.

A.

Maybe… maybe not.

Footnote: There is no guarantee that

this Blog does not contain elements of Unspeak.

Author: Alan J Taylor is a writer and critic who thinks about stuff and works as a Physiotherapist, University Assistant Professor

and Medico-Legal expert witness ... The views contained in this blog

are his own and are not linked to any organisation or institution. Like Bukowski, he 'writes to stay sane'. He once rode the Kellogs Tour of Britain and worked as a cycling soigneur.